Why You Should Strengthen Your Autistic Kid’s Thinking Skills

Thinking skills are necessary for independence, communication, and navigating social situations

By Jenny Burke, September 1, 2020

You might feel overwhelmed at the idea of taking a fresh look at your autistic child’s programming. But strengthening your child’s thinking skills should be a goal to be worked on both in and out of school. Yes parents, I mean you can work on this, too!

I speak from experience: helping our autistic child to build his thinking skills made a huge difference in so many ways, and I believe it would for your child as well.

Now, you might be thinking that I am making a big leap here from my child to yours, especially since no two kids with autism are the same. While that’s certainly true, take a look at this snapshot of my child to see if you can connect with anything. When he was younger, he did things like this:

- Screamed bloody murder over hot french fries or a missed shot on goal during pee wee soccer.

- Walked back and forth incessantly along walls; one stim (repetitive behavior) on a long list of many.

- Sang loudly during class and believed that other kids really actually did like his loud, non-stop singing because if they didn’t like it, they would for sure tell him.

- Often was not paying attention when others were talking because he didn’t understand them or was thinking about something way more interesting like the numbers cycling on a gas pump

- Insisted that I drive the exact same route to and from school, and when I took a different route, he’d get extremely upset.

- Absolutely would not under any circumstances eat off the plate with the yellow flower pattern.

It’s pretty clear that in addition to all his wonderful strengths—such a fantastic sense of humor, musical talent, and a really good nature—my child had significant challenges when it came to communication/language; flexibility; coping; managing intense sensory needs/aversions; and knowing what to say and do in social situations.

If you can relate to any of the above, this blog post is for you.

The infamous yellow plate. I recently busted my now 20-year-old son scraping pizza off this plate onto a plain brown one so he wouldn’t have to eat off of it.

Fast forward to today, Danny is an awesome young man who has made amazing progress. His expressive communication is pretty darn good, and he’s made great progress with receptive language. His social, coping, and problem-solving skills have improved so much. I was so proud when he told me recently he had on his own figured out a solution to a big challenge: keeping up with what a music tech instructor was saying in class (he decided to try a recording app on his phone). Further, his stimming behaviors are subtle and more “mainstream.”

I’m also happy to report that he is way more flexible. That said, to this day he’ll avoid that dang yellow flower plate like the plague!

Sure, he has ongoing challenges. I’m not going to paint a picture of perfection here because that would be untrue and unfair to other autism parents. He is a work-in-progress. But aren’t we all? I know I sure am.

Our autistic kiddo made amazing progress because we took an all hands on deck, multi-faceted approach to helping him with the challenges. This has included professional support; LOTS of effective intervention and structured programming both in and out of school; and, tons of parent involvement, (advocacy, homework help, and yes, even therapy and teaching).

Speech, occupational, sensory-based, and behavioral interventions along with social skills programming all were critical to Danny making so much progress. But as important were our efforts to build his active thinking skills, both through therapy and at home.

Building Danny’s thinking skills relied mainly on two methods. One was cognitive-behavioral-type visual work, thanks to an an extremely talented clinical psychologist with the Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Beth Anne Martin who did cognitive-behavioral and other types of therapeutic work with Danny during one-on-one sessions. If you choose to try cognitive-behavioral therapy for your child, you need to find a therapist who has good experience working with kids with autism, and that the therapy involves a lot of visual teaching. This is because autistic kids are often very concrete, “black and white” thinkers and visuals will greatly help with the process.

The second method was tons of at-home, informal, “in-the-moment” teaching by Tim (Danny’s dad and my husband) and me. It was Ellen Doller, a Ritchie McFarland Occupational Therapist (OT), and Danny’s amazing integrated preschool “Dream Team” who taught us the value of low-key, even fun in-the-moment teaching that takes place during unstructured time or daily routines as a means for helping a child make progress.

I cannot say enough about the difference at-home in-the-moment teaching has made for my autistic child. If you do the math, autistic kids are not in school or outside programming a lot of hours each week. All that time spent getting dressed, eating meals, driving somewhere, playing, etc., really add up when it comes to quick, informal teaching, reinforcement, and generalization opportunities for communication, social, and coping skills. As the OT, Ellen Doller said to me one time as she was working with my young child, “I am only with Danny twice a week for 45 minutes each time. You are the one who needs to interact with your child just like what I’m doing right now, and you need to be doing this all the time.” Parents, I’m not telling you to become a Ph.D., but I am urging you to take advantage of your child’s unstructured, at-home time!

As I go through the reasons why strengthening thinking skills matter so much, I’ll use examples to illustrate the two above approaches in action.

Here are the reasons why strengthening thinking skills helps a child make progress.

1. Thinking skills help with coping and problem-solving

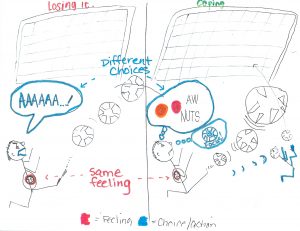

Dr. Martin and Danny drew this visual together to work on coping. She used thinking bubbles and talking balloons in her masterful work. Dr. Martin would be the first to agree that an adult need not have excellent drawing skills ☺.

Take Danny’s behavior of dealing with disappointment by screaming. Dr. Martin used the above visual as a tool to process with Danny his thoughts and feelings and to provide him with a schema or visual framework for how to handle these types of situations. She would emphasize it’s absolutely OK to feel disappointed, but that Danny could choose to react in a different way than screaming. In other words, Danny had to think about how he was feeling in a situation, and then think about how he would react, or, course correct; i.e., change his initial angry outburst to a more moderated one.

Dr. Martin’s and Danny’s visuals would come home so we could refer to them as needed. Also, we used Dr. Martin’s visuals as a model for new visuals that we would create to address other incidents of screaming or other melt-down-type behavior. Just like Dr. Martin, we’d engage Danny in the process of creating the visual. The use of visuals made a huge difference.

As a result, I am such a huge fan of using with autistic kids comic-book style visuals (with talking balloons and thinking bubbles) as a tool to work on all kinds of social and coping skills (they are great for receptive and expressive language work as well). (Check out Tips & Topics’, “After-the-Moment Teaching” for examples of this.) Be sure to check out Carol Gray’s Social Story model. Carol Gray has developed an autism-friendly, very specific process-based, visual tool for social learning.

Other visuals that can be helpful are: a visual that identifies the “triggers” for your child (e.g., thunder and lightening, large crowds) and a cartoon of your child engaging in a self-calming strategy.

Our in-the-moment teaching for increasing thinking skills to improve coping took many forms. We did a lot of describing of the triggers; i.e., what had caused Danny to become upset. For example, I might say, “Danny, this thunderstorm is very loud. You feel very scared.” Describing in real time to a child their thoughts and feelings is often a good first step in helping them understand better their thoughts and feelings and to be more self aware. (Describing is also a great in-the-moment teaching tool for building receptive language.)

Additional in-the-moment teaching by us involved prompting and reinforcing. Prompting was often in the form of what I call an indirect “thinking prompt.” If I could get away with it when Danny was upset, I would say things like, “What do you think you need right now?” or “You are having a strong feeling about the thunderstorm. What did Dr. Martin say you can do when you have a strong feeling?” Reinforcing essentially meant “catching,” or making a big deal, whenever he engaged in a positive coping behavior, like this: “Wow, I am so proud of you! I can tell you are feeling very disappointed you can’t go to the Science Center today, but you are coping with your disappointment! High-five!”

In-the-moment teaching also came in the form of holding off on giving help or even sneaky “sabotage” to force our kiddo to grapple with a problem. This piece nicely explains sabotage to promote communication and has great ideas. Here is a resource from our Tips & Topics content on using waiting as a strategy to encourage coping, communication, problem-solving, and independence.

Remember, coping with a problem, change, disappointment, a sensory challenge, or any strong feeling involves: self-awareness, choice-making, problem-solving, and communication. All of which require a person TO THINK!

Please note: for some children, a lack of functional coping behaviors stems from serious anxiety, depression, and/or another mental health challenge. Parents, if your child’s behaviors when upset are extreme and/or have somehow changed or worsened, please talk to your child’s pediatrician or a mental health provider, ideally one who specializes in children with autism. For more on this, check out this very helpful resource.

2. Thinking skills helps with interpreting and navigating social situations

I believe we do kids a huge disservice if we only teach social skills as discrete, separate behaviors. Of course we need to teach kids how to take turns, shake hands, or say “thank you” (we spent a lot of time working on such behaviors). But we also need to teach autistic kids to think about about what other people think and feel, especially in response to their words and actions.

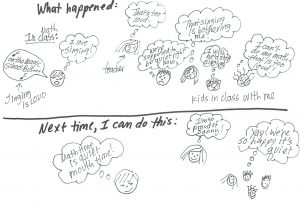

A lack of understanding that others can can think or feel differently can get a lot of people with autism in trouble socially, and this was certainly true for Danny. Consider him singing loudly in class, which was super disruptive. My child was not intentionally trying to bug the teacher and the other kids, he simply had no idea of how they felt about his singing. So, I made a visual to help him understand. This visual explanation of the others’ thoughts and feelings coupled with some great work by his school Speech Language Pathologist (SLP) made a huge difference in Danny keeping quiet during classtime.

Visuals like these really helped Danny grasp how others felt about his words and actions.

In addition to visual teaching, in-the-moment teaching was a big help in getting Danny to think about what others were thinking and feeling, and to adjust his own behaviors as a result. Consider Danny’s love of saying a joke over and over and over, to the great annoyance of others, usually his sister. I would say things like, “Danny, you think the joke is really funny. But Molly is feeling mad that you won’t stop telling it,” or “Molly, tell Danny how you are feeling right now that he won’t stop telling the joke.”

Pointing out in social situations the difference between what Danny and someone else was thinking or feeling was a very useful in-the-moment teaching technique that I learned from the “Dream Team.” Let’s say Danny and a preschool classmate wanted to play with the same toy, the Dream Teamers would say in the moment, “Danny is thinking about the bucket. Zach is thinking about the bucket, too! What can Danny say to Zach to get turn with the bucket?”

I am not suggesting here you skip social skills programming, especially when it is group-based. But the more you can build your child’s thinking skills, the better they will do in social situations.

3. Thinking skills help communication skills

When my autistic child was young, I had a saying: “Language is the key to the kingdom.” (If your child has minimal or no verbal abilities, swap out “language” and replace it with “communication.”) I felt that so much of his ability to make progress hinged on our maximizing his receptive language and expressive communication skills.

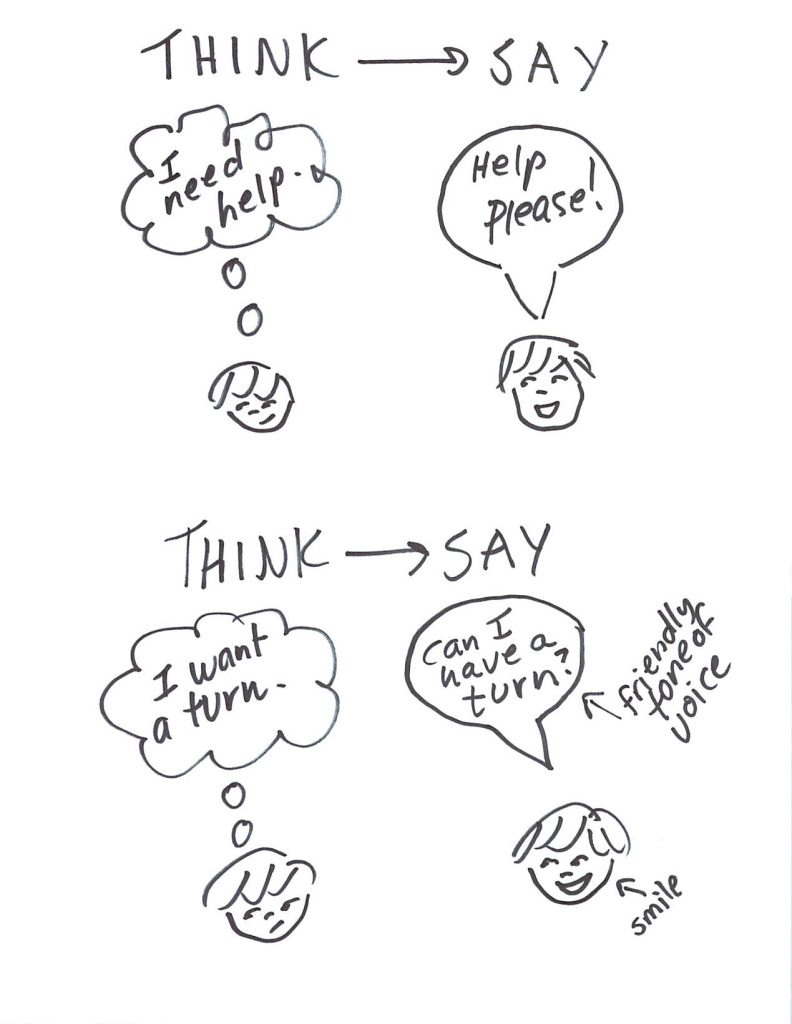

I love THINK-SAY. Parents, try this visual to help your kiddos build their coping, social, and communication skills.

Helping Danny improve his active thinking skills truly was a critical piece of him building communication. This visual here is exactly what we used to encourage expressive communication for a “need” or “want.” (By the way, there’s so much overlap, between the different skill areas. Asking for help is communication-based coping, and asking for a turn is a communication-based social skill.) Getting Danny to think first about what he needed or wanted really helped so much in getting him to then communicate that need or want.

And again, good old in-the-moment teaching during everyday life was huge for encouraging Danny to think in order to express himself, and then to reinforce him when he did. Let’s say my kiddo was not using language to ask for a drink, but instead was crying. I’d hold off on giving Danny the drink and say something like, “Danny, I do not know what you are thinking right now because you are not telling me.” While there were times where I might use a more direct verbal prompt such as “Say, ‘Drink, please,'” as Danny got older, I grew to favor more indirect “thinking prompts” (as I mentioned above) because they forced my child to, you guessed it, think! (In my resource about prompting, I discuss thinking prompts and give examples.)

A LOT of time and effort goes into helping a child, like mine, build communication skills. If your child has receptive and/or expressive challenges, talk to your child’s SLP about incorporating thinking skills into a plan to build communication.

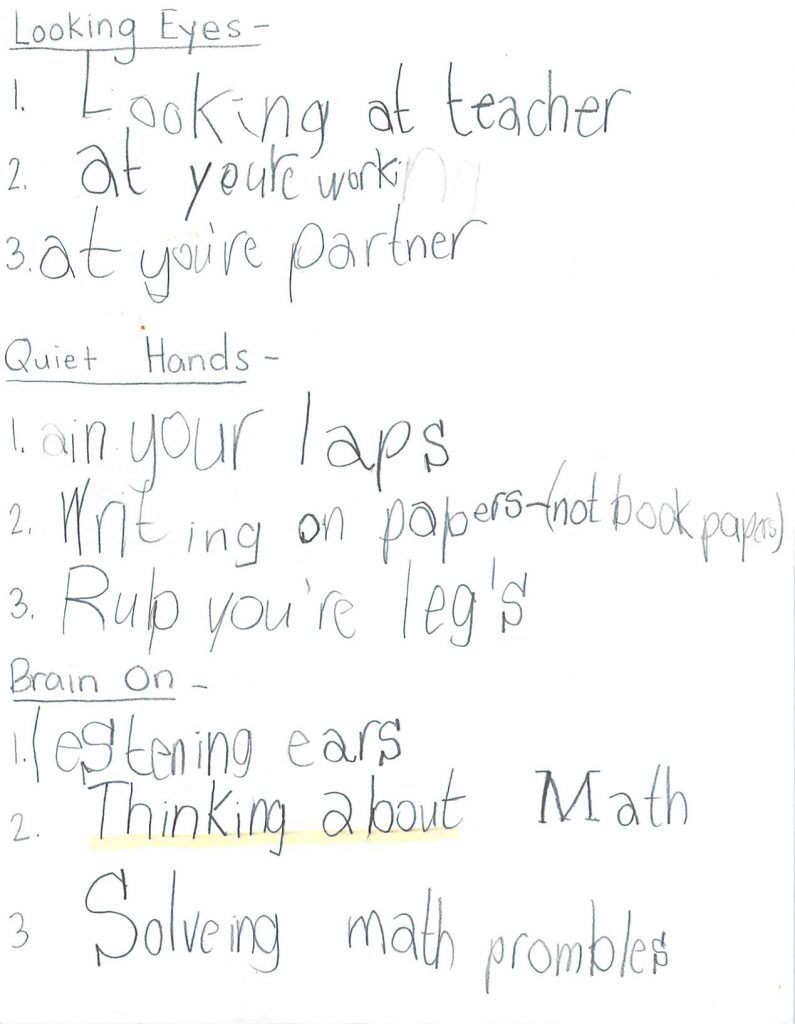

4. Thinking skills help with the ability to pay attention

When a teacher or other adult says to a child with autism, “Pay attention!” that kiddo might not have the slightest idea what the teacher wants them to do. This was certainly the case for Danny. Therefore, time and effort was dedicated to helping him to learn what paying attention actually means. Here is a visual where Dr. Martin did an awesome job breaking down with Danny the concept. Notice how thinking (“Brain on, thinking about math”) is an important element of paying attention.

Helping an autistic child to improve their focus and attending capabilities often requires a comprehensive approach that includes sensory-based interventions, therapy, and for some kids, possibly even medication. Additionally, kids who really struggle with this absolutely need supports to ensure they learn and make progress in school. Regardless, strengthening thinking skills should be part of the game plan.

5. Thinking skills help manage sensory input, boredom, or stress, which can help with stimming behaviors

“Stimming,” or self-stimulatory behavior, is a complicated, in-depth topic that deserves its own blog. Until I share my thoughts on raising an extremely stimmy kid, I think this article from Autism Parenting Magazine has clear information and solid advice.

While I can’t prove a causal connection between thinking skills and stimming, what I can say is that as we saw an increase in Danny’s skills and abilities (including thinking ones), we saw a decrease in certain stimming behaviors. So when Danny learned to cope by asking for help, say, with a zipper, he was less likely to get really upset and start wiggling his fingers. Or, when his receptive language skills improved such that he could follow simple dinner table conversation, he was less likely to tune out during a meal with a “wiper blade” arm swing. Or, when his social skills progressed to the point that it became easier and more enjoyable to play with another kid, he’d find playing chase preferable to walking alone back and forth along a wall.

Today, as a young man, all the stims from his younger years have been replaced with more “socially acceptable” activities like computer games. Making progress in all domains (e.g., communication, coping, social) have helped a ton with stimming. And, as I’ve said before, the reason Danny made such progress was definitely thanks in part to building his thinking skills.

What is the right approach for helping your child build their thinking skills?

The answer to this is that it totally depends on your own child’s needs and challenges. Maybe they would benefit from outside-of-school therapy that includes visually-based cognitive-behavioral work by a professional like Dr. Martin. Or, perhaps they are a great candidate for Michelle Garcia Winner’s Social Thinking Curriculum. Maybe your child’s school SLP and OT would be willing to incorporate strengthening thinking skills as a component of their work with your child. Your child might even be lucky enough to have teachers who already value metacognition—thinking about thinking—as a tool for learning. No matter what happens with your child in their therapies or at school, there’s still the opportunity to use in-the-moment teaching at home to practice critical thinking skills.

Regardless of your approach, take an active role, as you are the person who spends more time with your child than anyone else.

I LOVE this creation by Danny where he used a thinking bubble and talking balloons, but all these years later, I truly have no idea what it says!

I’d like to help, too! Find here affordable, visual tools for helping kids get better at being thinkers and expressing their thoughts, needs, and feelings. They use photos of real kids, have fun activities, and are great for building communication and social skills. And find here free resources for parents.

What about you? Have you had success with helping a child build their thinking skills?

Would your child eat off of that yellow plate? Please share!

Want to know when we post something new? Subscribe here.

Leave A Comment

Please be sure you understand our Comment Policy before posting a comment.You must be logged in to post a comment.